THE FIRST IGOROT PERFORMERS IN USA

IGOROTS IN THE 1900S WORLD'S FAIR

In the early 1900s, Filipinos were among the many people from around the world to be recruited to be part of public exhibits in the United States. Two men—Truman Hunt and Richard Schneidewind—recruited Igorots to join in the show, promising them money and travel. Although advertised as an opportunity to showcase their culture while earning a living, it proved to be more complicated, being away from home for long periods of time. Hunt, a former doctor and war veteran, treated the Igorots like a business opportunity, while Schneidewind (who had family ties to the Philippines) was more respectful, but still part of the entertainment trade. The travelers met harsh weather conditions and treatment they have not dealt with before, with some instances leading to sickness or death. Below is information about that time, their experiences, including videos from PBS & the Washington Post and an accompanying lesson plan.

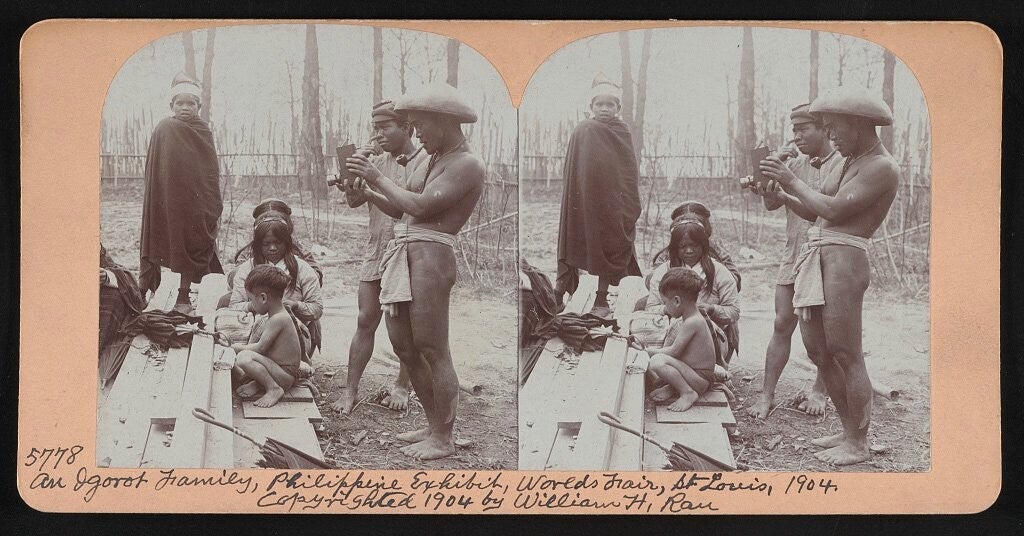

An Igorot family at the Philippine exhibit, World's Fair, St. Louis, 1904. This stereograph captures a moment of cultural display during the American colonial period, Library of Congress.

“An Igorot family, Philippine exhibit, World’s Fair, St. Louis, 1904.” Stereograph. Library of Congress Digital Collections.

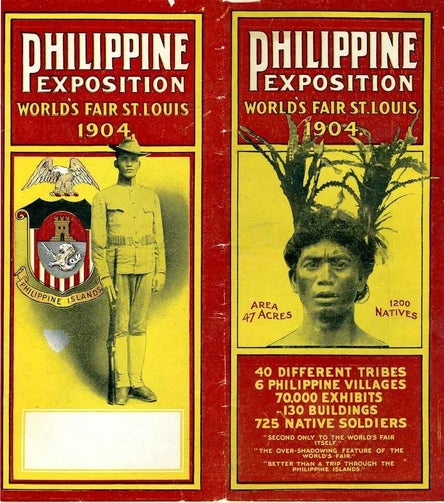

Truman Hunt, the former medical officer and lieutenant governor of Bontoc, first exhibited the Igorot people at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, in the “Philippine Reservation”. It was a great 47-acre display meant to showcase America’s new colonial subjects². The Igorot Village was the most popular attraction, drawing huge crowds. The recruited Igorot performers were under the impression they would be showcasing their daily life, and did not know that their Exhibit was part of this larger motive to reinforce rationalization that the US was meant to "civilize" the Philippines¹.

Following that success, Hunt brought a group of Igorots to Coney Island in 1905, where they were displayed at Luna Park and Dreamland Park¹ ³. These exhibitions were marketed as educational, but were essentially exploitative spectacles for Hunt to earn money. Hunt promised them monthly pay in exchange for their cultural performances.² ³

The Igorots were paid $15 a month²—a small sum considering the profits Hunt made—and they were required to perform exaggerated versions of their customs. Many suffered from poor nutrition, inadequate housing, and the emotional toll of being far from home and from being treated as entertainment ² ³. The working conditions were so troubling that in some cases, it lead to death.

The Igorots were displayed as “headhunters” and “dog-eaters,” labels to sensationalize them by Hunt and the American press to draw large crowds. Hunt orchestrated fake incidents—like dog thefts and staged fights—to reinforce the image of the Igorots as wild and uncivilized, a concept that helped rationalize or prioritize importance of American presence in the Philippines, their newly acquired colony. He even arranged for dogs from the New York pound to be cooked and served to the Igorots in public, turning rare ceremonial practice into a grotesque daily performance.² ³

Living in poor conditions and under constant scrutiny, the Igorots were paraded across the U.S. in sideshows and amusement parks. Hunt pocketed most of the profits, while the Igorots received little of the promised wages. His exploitation eventually led to his arrest in 1906 for embezzlement and abuse.⁴

🎪 From Fairgrounds to Human Zoos

The different productions the performers were part of:

-

1904 St. Louis World’s Fair: The Igorot Village was the most popular exhibit in the Philippine Reservation, drawing massive crowds. The Igorots were portrayed as “headhunting dog-eaters,” a narrative crafted to justify U.S. colonial rule.⁴

-

Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition (1905) and Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition (1909): The Igorots continued performing across the country, often under new managers like Richard Schneidewind.⁴

-

European tours: They were taken to Canada, Belgium, and other countries, where performances continued until tragedy struck in Ghent, Belgium, in 1913, when nine Igorots died from starvation⁵

Bain News Service. (1907, May 27). Filipinos in loin cloths sitting in circle together at Dreamland, Coney Island, N.Y. [Glass negative]. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014683953/

🐕 Rituals Turned Spectacle

At Coney Island, the Igorots were made to reenact tribal customs—often distorted for entertainment:

-

Dog feasts: A sacred ritual in the homeland was turned into a daily performance. Dogs were brought from the New York pound, butchered publicly, and served to the Igorots while crowds watched in fascination and horror.²

-

Mock weddings: These staged ceremonies were designed to exoticize their culture and reinforce stereotypes of primitiveness.²

-

Spear-throwing contests: Originally a display of skill and tradition, these were repackaged as “savage games” for American audiences.⁴

-

Singing and dancing: Traditional Igorot music and movement were performed regularly, stripped of context and repurposed as entertainment.²

After Hunt’s downfall, another organizer, Richard Schneidewind, took over. Unlike Hunt, Schneidewind treated the performers with more dignity, even housing them in his own home. He continued touring with them across the U.S. and Europe, but by 1913, the group was found starving in Ghent, Belgium. Nine Igorots had died, including five children. This prompted the U.S. government to intervene, repatriating the survivors, and banning future exhibitions of Filipino tribespeople abroad.⁵ The U.S. government banned future exhibitions of Filipino tribespeople abroad through an amendment to the Anti-Slavery Act in 1914.³

The Exhibits captivated millions, but left behind a legacy of exploitation, cultural distortion, and forgotten trauma. As National Geographic notes, the story forces us to reconsider who was truly “civilized” and how spectacle can obscure truth.²

Despite the trauma, some of the performers—like twelve-year-old Antero Cabrera—chose to remain in the U.S. and continued performing. Antero later became a translator and cultural ambassador, navigating the complex space between survival and self-representation.⁶ He sang “My Country ’Tis of Thee” at the White House and later became a translator and cultural ambassador. He helped create the first Bontoc-English dictionary and returned to the U.S. multiple times as part of performing troupes.⁷

PBS PRODUCTION - ANTERO'S STORY

Below is a video about the 1904 World's Fair-Exhibition of the Igorots that recaps the experience of the fair with interviews of historians and Antero's descendant, Mia Abeya.

Maura was one of the Igorot individuals taken to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and her story has become more popularly known through investigative reporting and community memory.

Maura was 18 years old when she was brought from the Kankanaey in Suyoc, Mankayan to be part of the “Igorrote Village” exhibit.⁸ She was displayed alongside other Filipinos in what was essentially a human zoo meant to showcase America’s colonial subjects.

Tragically, Maura died during the tour, and her brain was reportedly taken to the Smithsonian Institution’s Racial Brain Collection for pseudoscientific study.⁸ Her remains were never repatriated, and her story was forgotten until researchers and Igorot advocates began piecing together her life from oral histories and archival fragments.⁹ The investigators are of Filipino descent, and have come together from various parts of the world, in partnership with The Washington Post, to delve and share Maura's story. You can read more about the discovery of Maura in the link below:

SOURCES

1) DeCicco, T. (n.d.). The Igorot Village of Coney Island. Coney Island Museum. https://www.coneyislandmuseum.org/blog/the-igorot-village-of-coney-island

2) Qiu, L. (2014, October 28). Tribal headhunters on Coney Island? Author revisits disturbing American tale. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/141027-human-zoo-book-philippines-headhunters-coney-island

3) Prentice, C. (2014, October 14). The Igorrote tribe traveled the world for show and made these two men rich. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/igorrote-tribe-traveled-world-these-men-took-all-money-180953012/

4) Castro, A. R. (2024, June 25). Igorot headhunters inside America’s human zoos: The untold dark story. FilipiKnow. https://filipiknow.net/igorot-headhunters/

5) Prill-Brett, J. (2004). Voices from the other side: Impressions from some Igorot participants in U.S. cultural exhibitions in the early 1900s. The Cordillera Review, 1(1), 1–56. https://thecordillerareview.upb.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/3-TCR-I-1-Brett.pdf

6) The Asian American Education Project. (n.d.). 1904 World’s Fair—Exhibition of the Igorot Filipino People. https://asianamericanedu.org/1904-worlds-fair-exhibition-of-the-igorot-filipino-people.html

7) Sieber, K. (2019, July 6). Savages in the White House and the 1904 World’s Fair. Theodore Roosevelt Center. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Blog/Item/Savages%20in%20the%20White%20House%20and%20the%201904%20Worlds%20Fair

8) Basina, C. (2023, August 27). Getting to know Maura, the 18-year-old Igorot sent to take part in the 1904 World’s Fair. GMA News Online. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/lifestyle/content/880152/getting-to-know-maura-the-18-year-old-igorot-sent-to-take-part-in-the-1904-world-s-fair/story/

9) Dakopi. (2023, September 9). Maura’s story isn’t just about her; it’s about us, the Igorot people. Igorotage. https://www.igorotage.com/blog/p/w3enY/rediscovering-mauras-story