Who are the Igorots?

DEFINITION

A long time ago, people living in the highlands of northern Luzon didn’t call themselves “Igorot.” They identified by their villages—like Ifugao, Bontok, or Kankanaey. However, when Spanish colonizers arrived, they needed a name for these mountain communities. They borrowed the word “Igolot”, which came from golot, meaning “mountain chain,” and i, meaning “people of.” So “Igolot” meant “people of the mountains.”

Later, the spelling changed to “Igorot”, and Americans used it in official surveys. But not everyone liked the name. Some lowlanders used “Igorot” as an insult, and in 1958, Luis Hora, a congressman from the Mountain Province, tried to ban the word. Still, many highland groups began using “Igorot” proudly, reclaiming it as a symbol of identity.

"Igorot" is an umbrella term for the various ethno-linguistic indigenous tribes of what is now known today as the Cordillera Autonomous Region; an area previously labeled as Mountain Province by the United States government some time after attaining the Philippines from Spain with the Treaty of Paris (1898).

According to historian William Henry Scott , “Igorot” wasn’t a single tribe—it was a label created by outsiders that is also a word that tells a story of survival, resistance, and pride in being from the mountains.

THE ETHNOLINGUISTIC TRIBES

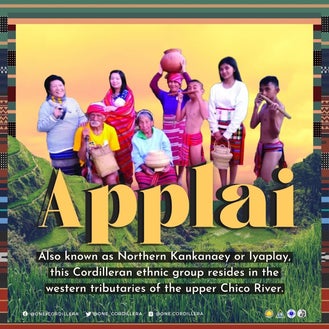

APPLAI

🌄 The Applai of Sagada and Besao

Nestled in the western tributaries of the upper Chico River, where mist clings to pine-covered ridges and the earth folds into ancient terraces, live the Applai—also known as Northern Kankanaey, Kankanaey, or Iyaplay. These highland people, the i-Sagada and i-Besao, carry with them a legacy as layered and resilient as the mountains they call home.

Linguists refer to their language as “Kankanay,” a variant distinct from its southern counterpart. Both Northern and Southern Kankanaey share a linguistic root, but the Applai speak with a “hard” intonation, a tonal strength that echoes the firmness of their stone-walled terraces and the cadence of their chants. Vocabulary shifts subtly between the two, but the rhythm of identity remains strong.

In the villages of Sagada and Besao, tradition is stitched into every thread of clothing. Northern Kankanaey women wrap themselves in red and black tapis accented with white, cinched at the waist with a bakget (white belt that marks their distinct style). The men wear the wanes, a g-string that speaks of ancestral pride and continuity.

The villages are structured around a dap-ay, a communal meeting hall that serves not only as a space for settling disputes and performing religious rites, but also as a male dormitory. The ebgan, houses the young women. This ward system, reminiscent of the Bontoc social organization, reflects a deep-rooted sense of community and shared responsibility.

Beyond the granaries and dormitories, their homes include four traditional types, among them the two-story innagamang, binang-iyan, tinokbob and the elevated tinabla—a testament to their ingenuity and adaptation to mountainous terrain.

They carved sloping terraces into the hillsides to grow rice and camote. In June or July, they plant topeng rice, and after the harvest in November or December, ginolot rice follows. When water runs low, camote steps in, ensuring sustenance through the dry spells.

📚 Sources:

-

Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera.

-

Longboan, L. C. (2011). E-gorots: Exploring Indigenous Identity in Translocal Spaces.

-

NCCA. (n.d). Peoples of the Philippines: Kankanay.

Photo and information adapted from One Cordillera

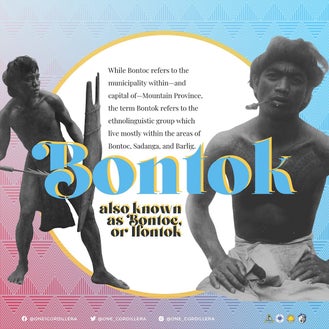

BONTOC

🌾 Folktale: Why the Bontok People Started Farming Rice

A long time ago in Alab, Bontoc, the land was full of gourds. People didn’t grow rice—they just ate the seeds from the gourds. Life was easy. Only a few men worked, and many others got by stealing from their neighbors.

Lumawig, a son of Kabunian that came down from the skyworld to live with the Igorot people, saw that this wasn’t fair. He wanted everyone to earn what they ate. So he made the gourd seeds taste bitter—so bitter that no one could eat them anymore. With no easy food, the people had to build rice terraces and work hard to grow rice. From then on, no one could live without working.

The Bontok people—also called Bontoc or Bontoc Igorot—live in the Mountain Province of the Cordillera region. Their name comes from two words: “bun” meaning heap, and “tuk” meaning top, which together mean “mountains.” While Bontoc is the name of the town, Bontok refers to the ethnolinguistic group found mostly in Bontoc, Sadanga, and Barlig.

📚 Sources:

-

Moss, E. (1974). Stories of the Bontoc Igorot People in Alab.

-

National Library of the Philippines Digital Collection.

-

National Commission on Culture and the Arts. Peoples of the Philippines: Bontoc.

-

U-M Library Digital Collections. Philippine Photographs Digital Archive.

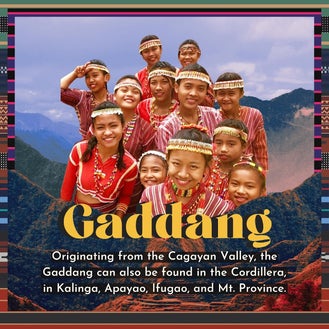

GADDANG

🧵 The Gaddang: Beads, Bravery, and Dance

The Gaddang—also known as Ga’dang, Kági, or Caggi—are from the Cagayan Valley, but you’ll also find them all over the Cordillera region, particularly in southeastern Kalinga and Apayao, Ifugao, and eastern Mountain Province.

What makes them stand out? Their clothing! Gaddang dress is full of colorful beads made from semiprecious stones. Just one look, and you can tell them apart from other Cordillera indigenous groups.

Traditionally, the Gaddang lived near streams and farmed rice, sweet potatoes, tobacco, and corn to sell.

Traditionally, leadership status was earned by respect: through bravery, skill, and knowledge of custom law. Wealth helped, too. They created peace pacts called pudon, and both men and women could lead rituals.

Like other Cordilleran groups, Gaddang men were expected to host at least one prestige feast in their lifetime. And of course, feasts meant dancing!

Here are some Gaddang dance moves:

-

Dumappa – arms raised at head level

-

Mangulafat – arms swaying at shoulder level

-

Malamano – hand shake

-

Misassad – traveling footwork

📚 Sources:

-

NCCA. Peoples of the Philippines: Ga’dang.

-

KWF (2021). Gáddang.

-

Parangal.org. . Ga’dang.

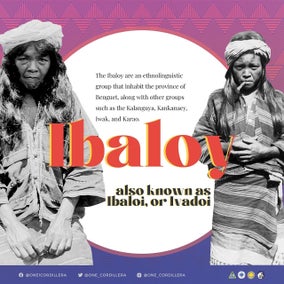

IBALOY

🍶 Folktale: How the Ibaloy Discovered Tapuy (Rice Wine)

Long ago, an Ibaloy woman was digging for camotes when she saw rice birds sleeping in her patch. She scooped them into her basket, planning to take them home—but before she could, they all flew away!

Curious, she realized the birds had eaten seeds from the angwad yeast plant, which must’ve made them sleepy. So she tried an experiment: she cooked rice and mixed in angwad seeds. Her dog ate some and got drunk. Then she tried it herself—and got drunk too.

That’s how the Ibaloy learned to make tapuy, the traditional rice wine.

🏡 Who Are the Ibaloy?

The Ibaloy—also called Ibaloi, Ibaluy, Nabaloi, Inavidoy, Inibaloi, or Ivadoi—live in Benguet province, alongside groups like the Iwak (also spelled Iowak or Owak), Kalanguya, Kankanaey, and Karao.

Their name comes from i- (meaning “people of”) and baloy (“house”), so Ibaloy means “people who live in houses.”

📚 Sources:

-

Cariño (2012), IFAD

-

Ballard (1972), Summer Institute of Linguistics

-

Fong (2016), Sunstar Philippines

-

NCCA (2017), The Ibaloi Tribe

-

U-M Library Digital Collections

IFUGAO

⛰️ How the Ifugao Say Mountains Were Made

Long ago, when Earth was flat, there were no hills or valleys. Kabigat, son of the Sky World god Wigan, came down from Hudog to hunt. His dogs ran so far chasing animals that he couldn’t even hear them bark. “The Earth must be flat,” Kabigat said, “because there’s no echo.”

He returned to the Sky World, then came back with a giant cloth, and used it to block the rivers from flowing into the sea. Then he asked Baiyuhibi, the god of rain, to make it pour for three days straight.

As the rain stopped, Wigan told Kabigat to remove the cloth, and the floodwaters rushed away, carving out valleys and pushing up mountains. That’s how the Ifugao say the Earth got its shape.

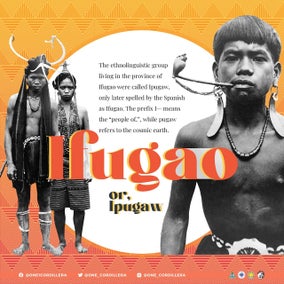

🌾 Who Are the Ifugao?

The Ifugao live in Ifugao province, where most towns are still mostly indigenous. They have three main subgroups: Tuwali, Ayangan, and Kalanguya (also called Kallahan). Their name comes from Ipugaw, meaning “people of the earth,” based on stories about Wigan of the Skyworld and Wigan of the Earth.

📚 Sources:

-

Beyer (1912), Origin Myths Among the Mountain Peoples of the Philippines

-

Lambrecht (1981), The Kalinga and Ifugaw Universe

-

Verzola (2007), Northern Dispatch

-

Princeton University Library

ITNEG

🐎 The Tingguian Lesson on Patience

One day, a man from the Tingguian (also called Itneg) loaded his horse with coconuts and set off for home. Along the way, he met a boy and asked, “How far is it to my house?”

The boy replied, “If you go slowly, you’ll get there soon. If you go fast, it’ll take all day.”

The man didn’t believe him and rushed ahead, and the coconuts kept falling off. He had to stop again and again to pick them up. By the time he got home, it was already night.

The Tingguian tell this story to remind people: sometimes, going slow gets you there faster.

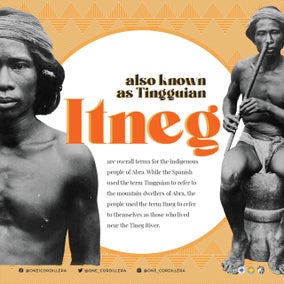

🏞️ Who Are the Tingguian or Itneg?

The Tingguian (from tinggi, meaning “mountain,” and -ngian, meaning “ancient”) are the indigenous peoples of Abra and parts of Ilocos. Spanish colonizers used “Tingguian” to describe mountain dwellers, but the people themselves use “Itneg” or “Itineg,” named after the Tineg River.

There are 11 subgroups in Abra:

-

Adasen, Balatok, Banao, Belwang, Binongan, Gubang, Illaud, Mabaka, Maeng, Masadiit, and Muyadan

📚 Sources:

Cariño, J. (2012). Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues: Republic of the Philippines. International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Cole, F. (1915). Traditions of the Tinguian: A Study in Philippine Folk-Lore. Project Gutenberg.

Cole, F. (1922). The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe. Project Gutenberg.

Verzola, P. (2007). “Mapping North Luzon’s indigenous peoples.” Northern Dispatch.

National Commission on Culture and the Arts. (n.d.). “Peoples of the Philippines: Tinggian.”

Photos courtesy of Princeton University Library

ISNEG

🌌 Why the Sky Is So High: An Isnag Story

Long ago, the sky was much closer to the ground. One day, an old Isnag woman was pounding rice, and her pestle kept hitting the sky. Each time she struck it, the sky moved higher and higher—until it finally stayed up where it is today.

That’s why, according to the Isnag, the sky is so far above us now: because of one determined rice-pounding woman.

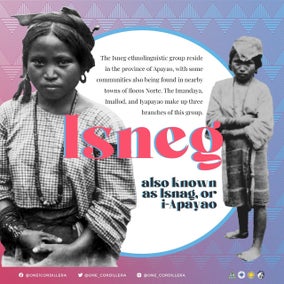

🏞️ Who Are the Isnag?

The Isnag—also called i-Apayao—live in Apayao province, with some communities in Ilocos Norte. Their name comes from is (“recede”) and uneg (“interior”), describing them as “people who went into the interior,” based on Spanish missionary accounts of their remote settlements near the Apayao River.

There are three Isnag branches:

-

Imandaya – “people upstream,” living in forested mountains

-

Imallod – those by rivers or coastal plains

-

Iyapayao – those on the Ilocos side

References:

Maranan, E. (n.d.). “The Isneg…”.

Vanoverbergh, M. (1955). Isneg Tales. Folklore Studies, 14, 1-148.

Verzola, P. (2007). “A list of Cordillera indigenous peoples groups.” Northern Dispatch.

Photo source:

Alexander Schadenberg

Portrait of a girl from Calanasan, Apayao, Northern Luzon, Philippines, 1876-1891. Museum of Ethnology, Dresden, Germany. Digital copy courtesy John Tewell.

Apayaos in Clalanasan, form. Bestand Berliner Anthropologische Gesellschaft, in the Besitz SMB-PK, Ethnologisches Museum Sammlung Ethnologisches Museum

IWAK

🐖 The Iwak and the Prestige Feast

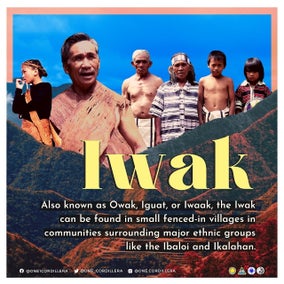

The Iwak—also known as Owak, Iguat, Iwaak, or Iowak—live in small, fenced-in villages near bigger Cordillera groups like the Ibaloi and Ikalahan. Whether in the highlands or lower areas like Nueva Vizcaya, the Iwak rely on farming. In the mountains, they grow taro and sweet potatoes; in the lowlands, they plant rice.

They also raise pigs—not just for food, but for tradition. Every Iwak man must host a padit, a personal prestige feast, at least once in his life. He gathers pigs for rituals, and the meat is carefully shared with the whole community.

It’s a way to show leadership, generosity, and respect.

📚 Sources:

NCCA. (n.d). Peoples of the Philippines: Iwak.

Wycliffe Bible Translators. (n.d). Iwak-Asia Philippines.

Cariño, J. (2012). Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples' Issues - Republic of the Philippines. International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Images from NCIP Benguet - AVP of Intergenerational Indigenous Peoples Attire Show for IWAK IP GROUP

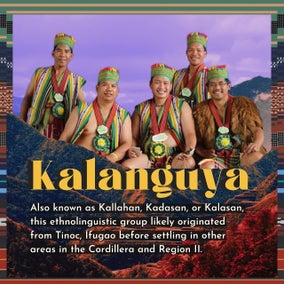

KALANGUYA

🌿 The Kalanguya: Peaceful Roots and Mountain Wisdom

According to nangkaama—the respected elders of the Kalanguya—their original home was Tinoc, Ifugao. But over time, they had to move because of bungkellew (plague) or ngayew (headhunting) from nearby groups.

The name Kalanguya might come from the phrase “Kelay ngo iya?” meaning “What in the world is this?”—a way to calm or correct someone. Others say it refers to their home in the mid-mountain forests of tropical oak.

The Kalanguya are known for their peaceful ways. Instead of going to court, they settle problems through:

-

Tongtong – a community discussion with arbiters and witnesses. The guilty party gives livestock for a guinnomon, a ritual to prevent future harm.

-

Kaihing – early betrothal between families to strengthen ties or settle disputes, often guided by the nangkaama.

Like other Ifugao groups, they grow taro and sweet potatoes, while rice is a prized crop. Pigs are also important, especially for rituals.

Though their simple lifestyle has made modern life harder, Kalanguya traditions now inspire global ideas about sustainability.

📚 Sources:

Cayat, G. (n.d). anuscript on Kalanguya Cultural Communities. NCCA.

NCCA. (n.d). Peoples of the Philippines: Ikalahan/Kalanguya.

Image of traditional Kalanguya attire from Teddy Baguilat, Jr.

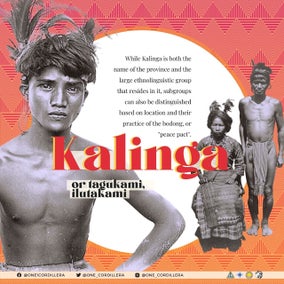

KALINGA

🌾 The Kalinga Legend of Rice and Responsibility

Long ago, according to the Kalinga people, rice didn’t need pounding—it came ready to cook from inside squashes! But a foolish man wanted dalkot, a sweeter kind of rice, so he greedily cut open squashes across many fields, wasting food and ruining harvests.

Kabuniyan (God) saw this and changed things. From then on, people had to plant and grow rice themselves.

Still, they were wasteful—burning extra rice they couldn’t eat, so Kabuniyan sent rats to eat everything. When the people cried out, Kabuniyan had mercy and sent cats to chase the rats away.

That’s how the Kalinga explain the origin of pagoy or pagey (unpounded rice) and why growing it takes hard work and care.

🛡️ Who Are the Kalinga?

Kalinga is both the name of the province and the ethnolinguistic group that lives there. In the Ibanag and Gaddang languages of Cagayan and Isabela, “Kalinga” means “enemy” or “headhunter,” based on past raids. Among themselves, the people call each other tagukami (“we are men”) or iLutakami (“we are people of the earth”).

Today, Kalinga refers to all indigenous groups in the province, though they’re also known by their towns, and bodong (peace pacts) are maintained between tribes.

📚 Sources:

References:

Billiet, F. (1934). A Kalinga Legend: The Origin of Unpounded Rice. Primitive Man, 7(1), 14.

Billiet, F. and Lambrecht, F. (1970). Studies on Kalinga Ullalim and Ifugao Orthography. Baguio City: The Catholic School Press. As cited in Matilac, R. (n.d.). “Kalinga…”

Lambrecht, F. H. (1981). The Kalinga and Ifugaw Universe. Ultimate Reality and Meaning, 4(1), 3-23.

Verzola, P. (2007). “A list of Cordillera indigenous peoples groups.” Northern Dispatch.

Photo source:

Dean C. Worcester Photographic Collection. "Young Kalinga Man." MIT Visualizing Cultures.

Princeton University Library.

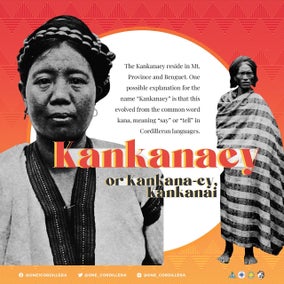

KANKANAEY

⚡ The Kankanaey Story of Thunder

Long ago, Comellab, a man from the Kankanaey, had a fight with Thunder. He asked, “Why do you strike animals, trees, and people?” Thunder replied, “I can strike anything I want—even crack rocks.”

So Comellab made a plan. He burned ginger, seashells, pepper, and human skulls. The smoke reached Thunder and his family in the sky, making them sick with rashes and stomachaches. Thunder came down to Earth, furious.

“You were cruel,” he said. “Now I’ll make a loud noise to scare you and your people.” That’s why thunder is so loud—and still strikes as it passes by.

🌄 Who Are the Kankanaey?

The Kankanaey (also spelled Kankana-ey or Kankanai) live in Mt. Province and Benguet. Their name may come from kana, meaning “say” or “tell.” Though their communities have different dialects, American scholars grouped them under one name because of shared culture and language.

📚 Sources:

The Teachers of Besao. (1974). THE LITERATURE OF BESAO. Philippine Sociological Review Vol 22 (No. 1), 135-149.

Verzola, P. (2007). “Mapping North Luzon’s indigenous peoples.” Northern Dispatch.

Photo source:

Philippine Journal of Science, 1906.

U-M Library Digital Collections. Philippine Photographs Digital Archive, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan.

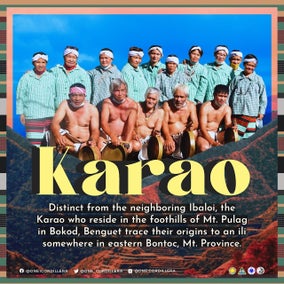

KARAO

🐍 The Karao: Snake Charmers of Mt. Pulag

Did you know the Karao, an indigenous group in Bokod, Benguet, are known as snake charmers? Living near Mt. Pulag, Karao men wear black bands on their lower left legs to stop snake bites. Their ancestors were said to live peacefully with snakes—so snakes don’t bite them.

The Karao originally came from an ili in eastern Bontoc, Mt. Province. After a deadly epidemic called banay a sahit or a natural disaster, they moved to Panuypuy, a lost village between the Awa and Matunu rivers in today’s Kayapa, Nueva Vizcaya. Eventually, they settled in Bokod.

📜 Ibaloi oral history says the Karao asked permission to live on Ibaloi land. The elders agreed, and the Karao moved near Mt. Pulag’s foothills.

Later, American colonizers grouped the Karao as Ibaloi. But the Karao have their own language, with a strong /ch/ sound, and traditions more like the Bontok—like separate dorms for boys and girls until they marry.

Today, the Karao are officially recognized as a distinct Indigenous People (IP). This helped them push for a proper Karao Orthography in schools, since earlier versions didn’t fit their language.

📚 Sources:

Reginaldo, J. (2021). The Ethnohistory of the Karao (I-karao) of the Southern Cordillera, Northern Luzon. The Cordillera Review.

Chanco-Salcedo, M. (1980). Feast and Ritual Among the Karao of Eastern Benguet. Social Science Information.

Image via NCIP Benguet. (2021). AVP on the Intergenerational Indigenous Peoples Attire for Karao IP Group.

Image and information adapted from One Cordillera