THE FIRST IGOROT PERFORMERS IN USA

IGOROTS IN THE 1900S WORLD'S FAIR

In the early 1900s, a group of Igorot people from the Philippines were brought to the United States to be part of public exhibits that showed their traditional way of life. Two men—Truman Hunt and Richard Schneidewind—organized these shows, promising the Igorots money and travel. Hunt, a former doctor and war veteran, treated the Igorots like a business opportunity, while Schneidewind (who had family ties to the Philippines) was more respectful, but still part of the entertainment trade.

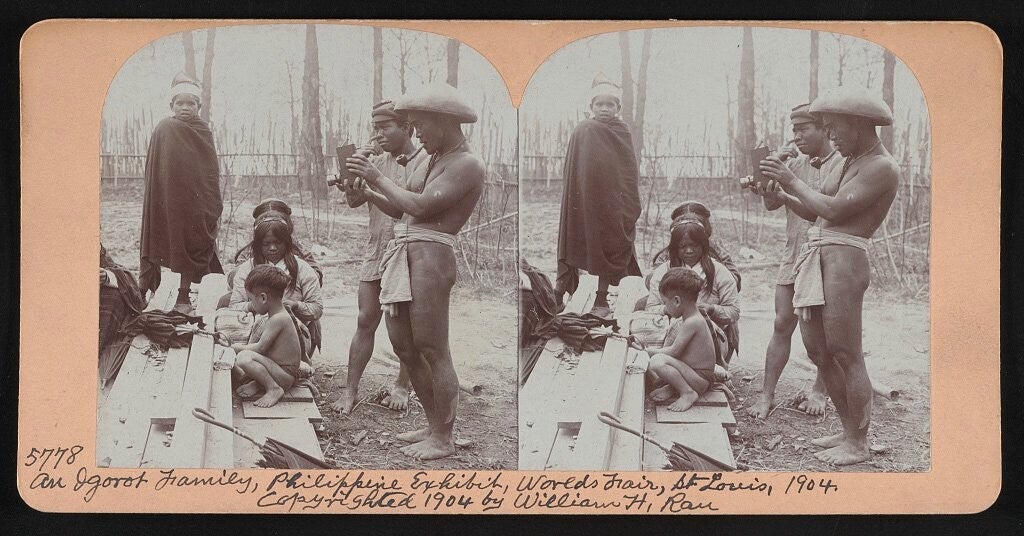

Truman Hunt, , the former lieutenant governor of Bontoc, first exhibited the Igorot people at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, in the “Philippine Reservation,” a great 47-acre display meant to showcase America’s new colonial subjects [2]. The Igorot Village was the most popular attraction, drawing huge crowds and reinforcing imperialist ideas about racial hierarchy and civilization [1].

Following that success, Hunt brought a group of Igorots to Coney Island in 1905, where they were displayed at Luna Park and Dreamland Park[1][3]. These exhibitions were marketed as educational but were essentially exploitative spectacles.

The Igorots were paid $15 a month [2]—a small sum considering the profits Hunt made—and were required to perform exaggerated versions of their customs, including mock dog feasts and tribal dances, often under harsh conditions. Many suffered from poor nutrition, inadequate housing, and the emotional toll of being far from home and treated as entertainment[3][2].

The working conditions were so troubling that eventually the U.S. government intervened, and the Philippine Assembly passed a law banning the overseas exhibition of Filipino tribes.

Sources:

In 1905, 50 Igorots from the Bontoc region—many of them young men and women—were recruited by Dr. Truman Hunt to perform at Coney Island’s Luna Park. Dr. Hunt was a former medical officer and lieutenant governor of Bontoc. Having gained the trust of the Igorots during his time in the Philippines, he was able to convince them to join him on an adventure to the United States to showcase the Igorot culture. He promised them $15 a month to be parts of these performances. What they didn’t know was that they were about to become the centerpiece of an exploitative spectacle that made him a rich man.

The Igorots were displayed as “headhunters” and “dog-eaters,” labels to sensationalize them by Hunt and the American press to draw large crowds. Hunt orchestrated fake incidents—like dog thefts and staged fights—to reinforce the image of the Igorots as wild and uncivilized, a concept that helped rationalize or prioritize importance of American presence in the Philippines, their newly acquired colony. He even arranged for dogs from the New York pound to be cooked and served to the Igorots in public, turning rare ceremonial practice into a grotesque daily performance.

🎪 From Fairgrounds to Human Zoos

Their performances weren’t limited to Coney Island:

-

1904 St. Louis World’s Fair: The Igorot Village was the most popular exhibit in the Philippine Reservation, drawing massive crowds. The Igorots were portrayed as “headhunting dog-eaters,” a narrative crafted to justify U.S. colonial rule.

-

Lewis & Clark Centennial Exposition (1905) and Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition (1909): The Igorots continued performing across the country, often under new managers like Richard Schneidewind.

-

European tours: They were taken to Canada, Belgium, and other countries, where performances continued until tragedy struck in Ghent, Belgium, in 1913, when nine Igorots died from starvation

🐕 Rituals Turned Spectacle

At Coney Island, the Igorots were made to reenact tribal customs—often distorted for entertainment:

-

Dog feasts: A sacred ritual in their homeland was turned into a daily performance. Dogs were brought from the New York pound, butchered publicly, and served to the Igorots while crowds watched in fascination and horror.

-

Mock weddings: These staged ceremonies were designed to exoticize their culture and reinforce stereotypes of primitiveness.

-

Spear-throwing contests: Originally a display of skill and tradition, these were repackaged as “savage games” for American audiences.

-

Singing and dancing: Traditional Igorot music and movement were performed regularly, stripped of context and repurposed as entertainment.

Living in poor conditions and under constant scrutiny, the Igorots were paraded across the U.S. in sideshows and amusement parks. Hunt pocketed most of the profits, while the Igorots received little of the promised wages. His exploitation eventually led to his arrest in 1906 for embezzlement and abuse

After Hunt’s downfall, another organizer, Richard Schneidewind, took over. Unlike Hunt, Schneidewind treated the Igorots with more dignity, even housing them in his own home. He continued touring with them across the U.S. and Europe. But by 1913, the group was found starving in Ghent, Belgium. Nine Igorots had died, including five children. The U.S. government intervened, repatriating the survivors and banning future exhibitions of Filipino tribespeople abroad.

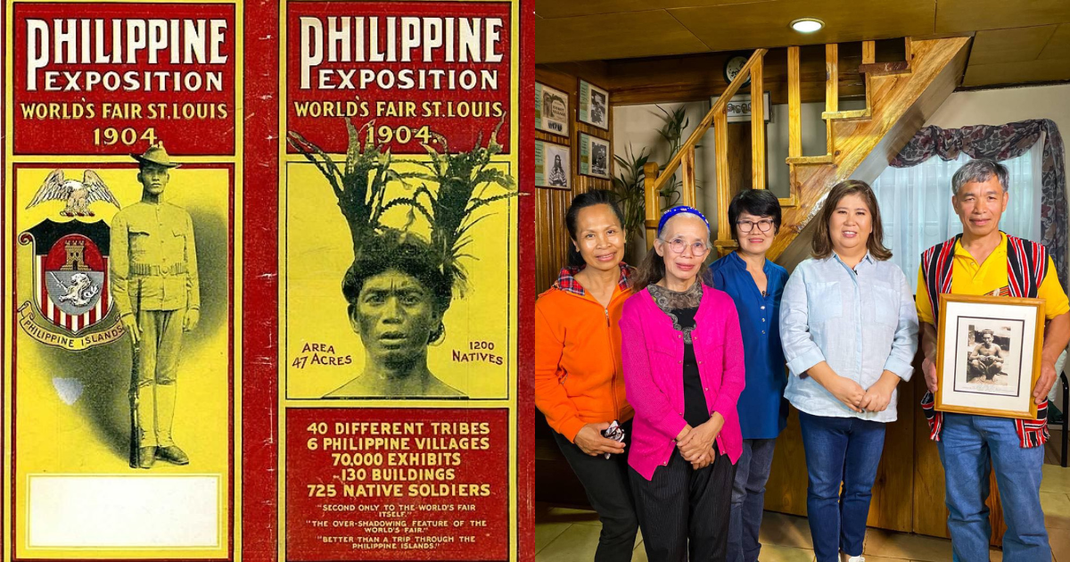

Despite the trauma, some Igorots—like twelve-year-old Antero Cabrera—chose to remain in the U.S. and continued performing. Antero later became a translator and cultural ambassador, navigating the complex space between survival and self-representation.

🎤 Antero Cabrera: From Performer to Cultural Bridge

Among the Igorots was twelve-year-old Antero Cabrera, who sang “My Country ’Tis of Thee” at the White House and later became a translator and cultural ambassador. He helped create the first Bontoc-English dictionary and returned to the U.S. multiple times as part of performing troupes.

The legacy of these exhibitions is haunting. The Igorots were reduced to caricatures of savagery to justify American colonial rule. Their real lives, cultures, and dignity were obscured by spectacle. Yet their resilience, and the efforts of descendants and historians to reclaim their stories, continue to challenge the narratives imposed upon them.

Since most of the money went to the organizers, and not the Igorots. Over time, the tribespeople were left poor, hungry, and far from home. Some even died during the tours. Eventually, the U.S. government stepped in after reports of mistreatment, and the Philippine Assembly passed a law banning the overseas exhibition of Filipino tribes. The story raises important questions about exploitation, cultural respect, and how Indigenous people were treated during colonial times

🌍 The Igorot Exhibitions: A Tale of Exploitation and Spectacle

In the early 1900s, a group of Bontoc Igorots were brought to the United States to be displayed in public exhibitions. These events, often staged in amusement parks like Coney Island, were part of a broader trend of “human zoos” that sensationalized non-Western cultures for entertainment and political propaganda. The Igorots performed dances, rituals, and even mock dog feasts at places like Coney Island and world expos. Millions of Americans came to watch, and the shows made a lot of money. Journalist Claire Prentice wrote a book called, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century. covering the story of how a group of Igorot people from the Philippines were brought to the U.S. in 1905 by showman Truman K. Hunt.

🎭 The Spectacle at Coney Island

In 1905, Truman Hunt, a former medical doctor and lieutenant governor of Bontoc, recruited 50 Igorots to perform tribal rituals—including dog feasts and mock ceremonies—at Coney Island. The performances were exaggerated and distorted versions of their actual customs, designed to shock and entertain American audiences2. Promising them adventure and income, Hunt instead exploited them in a human zoo-style exhibit at Luna Park in Coney Island, where they performed traditional tribal rituals—including mock dog feasts and headhunting tales—for massive crowds. Hunt promised the Igorots $15 a month, but he quickly turned their culture into a commodity, profiting immensely while the tribespeople lived in poor conditions and received little of the earnings.

As the Igorots performed, Hunt grew rich—but his greed and deception led to scandal. He fled across America with the tribe, pursued by detectives, creditors, and government agents. Claire's book explores themes of colonialism, cultural exploitation, and the blurred line between entertainment and abuse, all set against the backdrop of America’s fascination with “exotic” peoples during the early 20th century2.

📰 Media Manipulation and Mythmaking

Hunt controlled the narrative, feeding sensational stories to the press. He fabricated incidents, such as violent clashes and dog thefts, to portray the Igorots as “savages” and boost ticket sales. Newspapers across the country echoed his tales, reinforcing racist stereotypes and justifying American colonial rule by portraying Filipinos as unfit for self-governance2.

⚔️ Rivalry and Scandal

Hunt’s success attracted competition. Richard Schneidewind, another Spanish-American War veteran, brought his own Igorot troupe to the U.S. Unlike Hunt, Schneidewind treated his group more like family, even inviting them into his home. The rivalry escalated, culminating in Hunt’s arrest in 1906 for embezzling wages and mistreating the Igorots. He was sentenced to 18 months in a Memphis workhouse1.

🌐 Global Tours and Collapse

Schneidewind continued the exhibitions, touring the U.S. and later Europe. But by 1913, his group was found starving in Ghent, Belgium. Nine members had died, including five children. The U.S. government intervened, repatriating the survivors and banning future exhibitions of Filipino tribespeople abroad through an amendment to the Anti-Slavery Act in 1914.

🧠 Cultural Legacy and Reflection

These exhibitions were part of a larger colonial strategy to depict Filipinos as primitive, reinforcing the U.S. narrative of benevolent occupation. The Igorot shows captivated millions but left behind a legacy of exploitation, cultural distortion, and forgotten trauma. As National Geographic notes, the story forces us to reconsider who was truly “civilized” and how spectacle can obscure truth.

Maura was one of the Igorot individuals taken to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and her story has become more popularly known through investigative reporting and community memory.

According to The Washington Post and other sources, Maura was 18 years old when she was brought from the Kankanaey community in Suyoc, Mankayan to be part of the “Igorrote Village” ex hibit [1]. She was displayed alongside other Indigenous Filipinos in what was essentially a human zoo meant to showcase America’s colonial subjects.

Tragically, Maura died during the tour, and her brain was reportedly taken to the Smithsonian Institution’s Racial Brain Collection for pseudoscientific study [1]. Her remains were never repatriated, and her story was forgotten until researchers and Igorot advocates began piecing together her life from oral histories and archival fragments [2].

Her case has become a powerful symbol of the exploitation and erasure faced by Indigenous Filipinos during the colonial era—and a call to honor their memory and reclaim their narratives.