The First Igorot Tribe in America

Journalist Claire Prentice wrote a book called, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century., which covers the story of how a group of Igorot people from the Philippines were brought to the U.S. in 1905 by showman Truman K. Hunt, the former lieutenant governor of Bontoc.

Promising them adventure and income, Hunt instead exploited the in a human zoo-style exhibit at Luna Park in Coney Island, where they performed traditional tribal rituals—including mock dog feasts and headhunting tales—for massive crowds.

As the Igorots performed, Hunt grew rich—but his greed and deception led to scandal. He fled across America with the tribe, pursued by detectives, creditors, and government agents. The book explores themes of colonialism, cultural exploitation, and the blurred line between entertainment and abuse, all set against the backdrop of America’s fascination with “exotic” peoples during the early 20th century.

In the early 1900s, a group of Igorot people from the Philippines were brought to the United States to be part of a public exhibit that showed their traditional way of life. Two men—Truman Hunt and Richard Schneidewind—organized these shows, promising the Igorots money and travel. Hunt, a former doctor and war veteran, treated the Igorots like a business opportunity, while Schneidewind (who had family ties to the Philippines) was more respectful, but still part of the entertainment trade.

The Igorots performed dances, rituals, and even mock dog feasts at places like Coney Island and world expos. Millions of Americans came to watch, and the shows made a lot of money. Most of the money went to the organizers, and not the Igorots. Over time, the tribespeople were left poor, hungry, and far from home. Some even died during the tours.

Eventually, the U.S. government stepped in after reports of mistreatment, and the Philippine Assembly passed a law banning the overseas exhibition of Filipino tribes. The story raises important questions about exploitation, cultural respect, and how Indigenous people were treated during colonial times

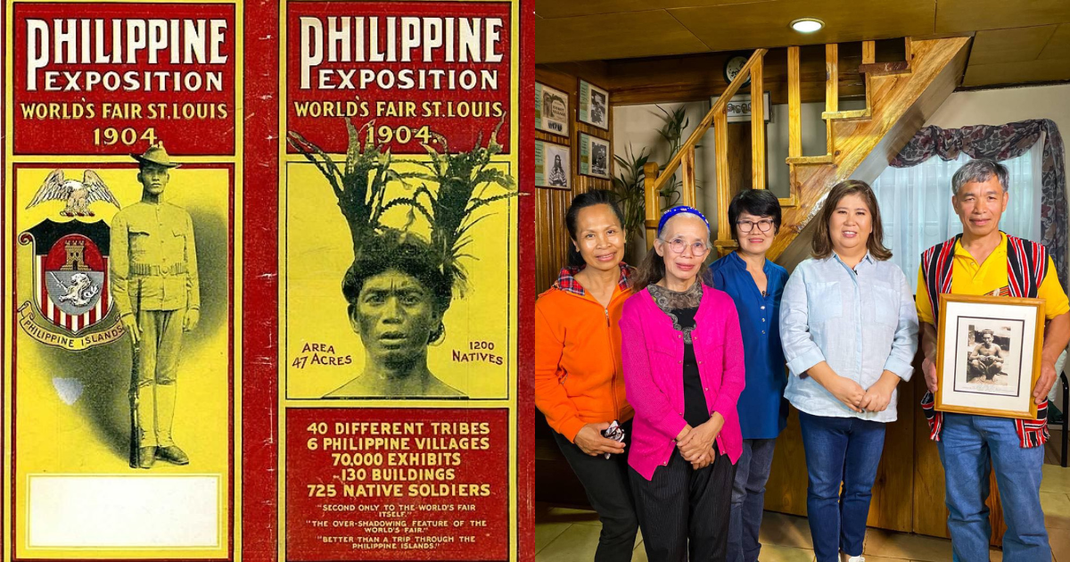

Truman Hunt first exhibited the Igorot people at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, in the “Philippine Reservation,” a great 47-acre display meant to showcase America’s new colonial subjects [2]. The Igorot Village was the most popular attraction, drawing huge crowds and reinforcing imperialist ideas about racial hierarchy and civilization [1].

Following that success, Hunt brought a group of Igorots to Coney Island in 1905, where they were displayed at Luna Park and Dreamland Park[1][3]. These exhibitions were marketed as educational but were essentially exploitative spectacles. The Igorots were paid $15 a month [2]—a small sum considering the profits Hunt made—and were required to perform exaggerated versions of their customs, including mock dog feasts and tribal dances, often under harsh conditions. Many suffered from poor nutrition, inadequate housing, and the emotional toll of being far from home and treated as entertainment[3][2].

The working conditions were so troubling that eventually the U.S. government intervened, and the Philippine Assembly passed a law banning the overseas exhibition of Filipino tribes.

Sources:

Maura was one of the Igorot individuals taken to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, and her story has become more popularly known through investigative reporting and community memory.

According to The Washington Post and other sources, Maura was 18 years old when she was brought from the Kankanaey community in Suyoc, Mankayan to be part of the “Igorrote Village” exhibit [1]. She was displayed alongside other Indigenous Filipinos in what was essentially a human zoo meant to showcase America’s colonial subjects.

Tragically, Maura died during the tour, and her brain was reportedly taken to the Smithsonian Institution’s Racial Brain Collection for pseudoscientific study [1]. Her remains were never repatriated, and her story was forgotten until researchers and Igorot advocates began piecing together her life from oral histories and archival fragments [2].

Her case has become a powerful symbol of the exploitation and erasure faced by Indigenous Filipinos during the colonial era—and a call to honor their memory and reclaim their narratives.